TO: Administrative File: CAG-00439N

FROM: Tamara Syrek Jensen, JD

Director,

Coverage and Analysis Group

Joseph Chin, MD, MS

Acting Deputy Director,

Coverage and Analysis Group

Lori Ashby

Acting Director, Division of Medical and Surgical Services

Joseph Hutter, MD, MA

Medical Officer

Jamie Hermansen, MPP

Lead Health Policy Analyst

SUBJECT: Proposed Decision Memorandum on Screening for Lung Cancer with Low Dose Computed Tomography (LDCT)

DATE: November 10, 2014

I. Proposed Decision

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) proposes that the evidence is sufficient to add a lung cancer screening counseling and shared decision making visit, and for appropriate beneficiaries, screening for lung cancer with low dose computed tomography (LDCT), once per year, as an additional preventive service benefit under the Medicare program only if all of the following criteria are met:

Beneficiary eligibility criteria:

- Age 55-74 years;

- Asymptomatic (no signs or symptoms of lung disease);

- Tobacco smoking history of at least 30 pack-years (one pack-year = smoking one pack per day for one year; 1 pack = 20 cigarettes);

- Current smoker or one who has quit smoking within the last 15 years; and

- A written order for LDCT lung cancer screening that meets the following criteria:

- For the initial LDCT lung cancer screening service: the beneficiary must receive a written order for LDCT lung cancer screening during a lung cancer screening counseling and shared decision making visit, furnished by a physician [as defined in Section 1861(r)(1) of the Social Security Act (the Act)] or qualified non-physician practitioner (physician assistant, nurse practitioner, or clinical nurse specialist as defined in §1861(aa)(5) of the Act).

- For subsequent LDCT lung cancer screenings: the beneficiary must receive a written order, which may be furnished during any appropriate visit (for example: during the Medicare annual wellness visit, tobacco cessation counseling services, or evaluation and management visit) with a physician (as defined in Section 1861(r)(1) of the Act) or qualified non-physician practitioner (physician assistant, nurse practitioner, or clinical nurse specialist as defined in Section 1861(aa)(5) of the Act).

- A lung cancer screening counseling and shared decision making visit includes the following elements (and is appropriately documented in the beneficiary’s medical records):

- Determination of beneficiary eligibility including age, absence of signs or symptoms of lung disease, a specific calculation of cigarette smoking pack-years; and if a former smoker, the number of years since quitting;

- Shared decision making, including the use of one or more decision aids, to include benefits, harms, follow-up diagnostic testing, over-diagnosis, false positive rate, and total radiation exposure;

- Counseling on the importance of adherence to annual LDCT lung cancer screening, impact of comorbidities and ability or willingness to undergo diagnosis and treatment;

- Counseling on the importance of maintaining cigarette smoking abstinence if former smoker, or smoking cessation if current smoker and, if appropriate, offering additional Medicare-covered tobacco cessation counseling services; and

- If appropriate, the furnishing of a written order for lung cancer screening with LDCT. Written orders for both initial and subsequent LDCT lung cancer screenings must contain the following information, which must also be

documented in the beneficiaries’ medical records:

- Beneficiary date of birth,

- Actual pack-year smoking history (number);

- Current smoking status, and for former smokers, the number of years since quitting smoking;

- Statement that the beneficiary is asymptomatic; and

- NPI of the ordering practitioner.

Radiologist eligibility criteria:

- Current certification with the American Board of Radiology or equivalent organization;

- Documented training in diagnostic radiology and radiation safety;

- Involvement in the supervision and interpretation of at least 300 chest computed tomography acquisitions in the past 3 years; and

- Documented participation in continuing medical education in accordance with current American College of Radiology standards.

Radiology imaging center eligibility criteria:

For purposes of Medicare coverage of lung cancer LDCT screening, an eligible LDCT screening facility is one that:

- Has participated in past lung cancer screening trials, such as the National Lung Screening Trial, or an accredited advanced diagnostic imaging center with training and experience in LDCT lung cancer screening;

- Must use LDCTs with an effective radiation dose less than 1.5 mSv; and

- Must collect and submit data to a CMS-approved national registry for each LDCT lung cancer screening performed. The data collected and submitted to a CMS-approved national registry must include, at minimum, all of the following elements:

| Data Type |

Minimum Required Data Elements |

|---|

| Facility |

Identifier |

| Radiologist (reading) |

National Provider Identifier (NPI) |

| Patient |

Identifier |

| Ordering Practitioner |

National Provider Identifier (NPI) |

| Demographics |

Date of birth, gender, race/ethnicity. |

| Indication |

Lung cancer LDCT screening – absence of signs or symptoms (y/n) |

| Smoking history |

Current status (current, former, never),

If former smoker, years since quitting,

Pack-years as reported by the ordering practitioner. |

| CT scanner |

Manufacturer, Model. |

| Effective radiation dose |

CT dose index, tube current-time, tube voltage, scanning time, scanning volume, pitch, slice thickness (collimation). |

| Screening exam results |

Baseline or repeat screen;

Screen date;

Clinically significant non-lung cancer findings (y/n), if yes, list;

Nodule (y/n), if yes: number, type (calcified or non-calcified; solid or semi-solid), size and location of each nodule. |

| Diagnostic follow-up of abnormal findings within 1 year |

Low dose chest CT,

Diagnostic chest CT,

Bronchoscopy,

Non-surgical biopsy,

Resection (with dates),

Other (please specify). |

| Lung cancer incidence within 1 year |

Incident cancers,

Date of diagnosis,

Stage,

Histology,

Period of follow-up for

incidence. |

| Health outcomes |

All cause mortality,

Lung cancer mortality,

Death within 60 days after most invasive diagnostic procedure.

|

For purposes of Medicare coverage of LDCT lung cancer screening, national registries interested in seeking CMS approval must send a request either electronically or hard copy to CMS (Note: It is not necessary to submit both electronic and hard copies of requests).

Please send electronic requests via email to caginquiries@cms.hhs.gov. Hard copy requests may be sent to the following address:

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

Center for Clinical Standards and Quality

Director, Coverage and Analysis Group

ATTN: Lung Cancer LDCT Screening

Mail Stop: S3-02-01

7500 Security Blvd.

Baltimore, MD 21244

CMS is seeking comments on the proposed decision. We will respond to public comments in a final decision memorandum, as required by §1862(l)(3) of the Social Security Act.

II. Background

Throughout this document we use numerous acronyms, some of which are not defined as they are presented in direct quotations. Please find below a list of these acronyms and corresponding full terminology.

AAFP – American Academy of Family Physicians

ACR – American College of Radiology

ALA – American Lung Association

CAT – computerized axial tomography

CCI – Charlson comorbidity index

CT – computed tomography

CXR – chest x-ray

DANTE – Detection and Screening of Early Lung Cancer by Novel Imaging Technology Molecular Assays

DLCST – Danish Lung Cancer Screening Trial

FDA – United States Food and Drug Administration

FDCA – Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act

JNCCN – Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network

LC – lung cancer

LDCT – low dose computed tomography

MCBS – Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey

MILD – Multicentric Italian Lung Detection

NCCN – National Comprehensive Cancer Network

NCI – National Cancer Institute

NCRP – National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements

NIH – National Institutes of Health

NLST – National Lung Screening Trial

NSCLC – non-small cell lung cancer

PLCO – Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial

PMA – premarket approval application

PPV – positive predictive value

RCT – randomized control trial

SEER – Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

USPSTF – United States Preventive Services Task Force

CMS initiated this national coverage determination (NCD) to consider coverage under the Medicare Program for lung cancer screening with low dose computed tomography (LDCT). The scope of our review is limited to the consideration of screening for lung cancer with LDCT. Diagnostic CTs are outside the scope of this national coverage analysis.

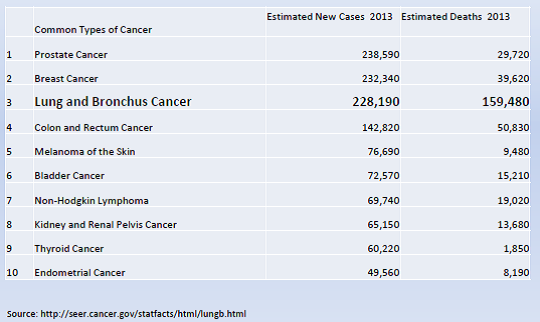

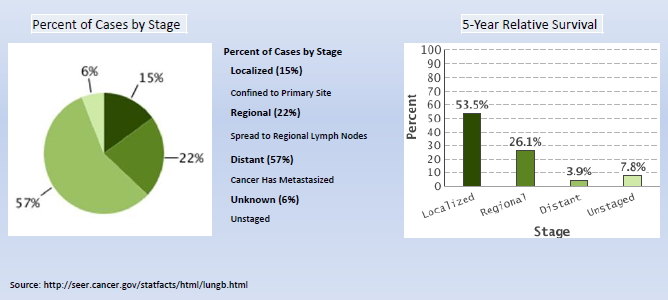

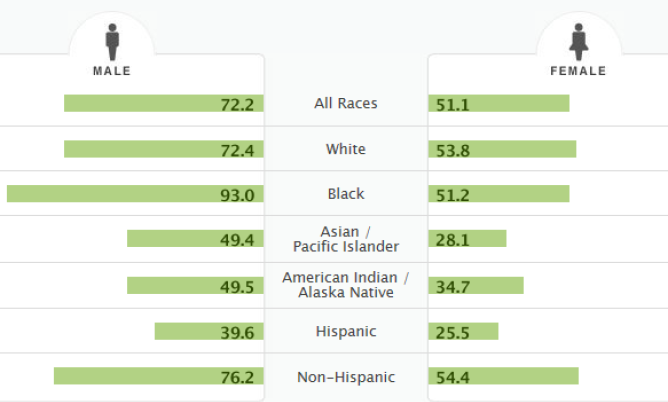

Lung cancer (LC) is the third most common cancer and the leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States. It is an important issue for the Medicare population due to the age at diagnosis and at death. In 2013, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) estimated that the number of new cases is over 220,000, with a median age at diagnosis of 70 years. Cancer of the lung and bronchus accounted for over 150,000 deaths in 2013 (more than the total number of deaths from colon, breast and prostate cancer combined) with a median age at death of 72 years.

Overall mortality rates for lung and bronchus cancer has decreased only slightly over the past decade. The majority of cases are still diagnosed at a late stage with a low five-year relative survival. (NIH/NCI/SEER 2013).

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Cancer Institute (NCI) describes computed tomography (CT) as “an imaging procedure that uses special x-ray equipment to create detailed pictures, or scans, of areas inside the body. It is also called computerized tomography and computerized axial tomography (CAT). Most modern CT machines take continuous pictures in a helical (or spiral) fashion rather than taking a series of pictures of individual slices of the body, as the original CT machines did. Helical CT has several advantages over older CT techniques: it is faster, produces better 3-D pictures of areas inside the body, and may detect small abnormalities better. The newest CT scanners, called multislice CT or multidetector CT scanners, allow more slices to be imaged in a shorter period of time.” (NIH/NCI; http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/Detection/CT)

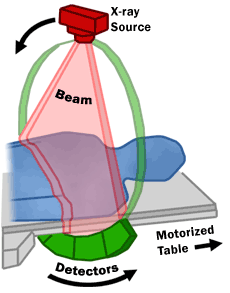

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) describes the mechanisms of a CT scanner as follows (also see image below): “A motorized table moves the patient through a circular opening in the CT imaging system. While the patient is inside the opening, an X-ray source and a detector assembly within the system rotate around the patient. A single rotation typically takes a second or less. During rotation, the X-ray source produces a narrow, fan-shaped beam of X-rays that passes through a section of the patient's body. Detectors in rows opposite the X-ray source register the X-rays that pass through the patient's body as a snapshot in the process of creating an

image. Many different "snapshots" (at many angles through the patient) are collected during one complete rotation. For each rotation of the X-ray source and detector assembly, the image data are sent to a computer to reconstruct all of the individual "snapshots" into one or multiple cross-sectional images (slices) of the internal organs and tissues.”

(US Food and Drug Administration (FDA); http://www.fda.gov/Radiation-EmittingProducts/RadiationEmittingProductsandProcedures/MedicalImaging/MedicalX-Rays/ucm115317.htm)

LDCT is a chest CT scan performed at acquisition settings to minimize radiation exposure, currently targeted at ≤ 1.5 mSv (the equivalent of 15 chest x-rays), compared to a standard chest CT with a median radiation dose of 8 mSv (Smith-Bindman, 2009). As a comparison, the National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements (NCRP) reported that in 2006, the average annual radiation exposure from natural sources in the United States was about 3.1 mSv (Schauer, 2009). Prasad et al. (2002) noted: “[s]everal factors influence patient radiation dose from CT including tube voltage, tube current, scanning time, pitch, slice thickness, and scanning volume. Radiation dose is linearly related to tube current, scanning time, and scan volume and inversely related to pitch. Although scanning times are decreased on modern helical CT scanners, the radiation dose associated with helical scanners is greater than that of other imaging procedures because of the increased tube current and volume of tissue irradiated.”

While LDCT reduces radiation exposure, image quality is also reduced which in turn may influence readability. Bankier and Tack (2010) noted: “[t]he concept of reducing the radiation dose in chest CT was first introduced by Naidich et al., (1990) who reduced the tube current on incremental 10-mm collimation CT and showed that with tube current settings as low as 20 mAs, the image quality is sufficient for assessing the lung parenchyma. Although these images were sufficient for diagnostically assessing the lung parenchyma, the increased image noise resulted in marked degradation of the quality of images on mediastinal window settings.”

Given the burden of lung cancer on the United States population, a suitable screening test for lung cancer has been sought for many years. The earliest studies were conducted in the 1960’s and 1970’s, testing sputum cytology and chest radiography or a combination of both. The initial studies using sputum cytology and/or chest radiography tests failed to conclusively demonstrate improvements in health outcomes, leading the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) to give lung cancer screening a grade D recommendation in 1985 and again in 1996 (Humphrey, 2004). Low dose helical computed tomography began being considered for use as a screening modality starting in the 1990’s. Naidich et al. (1990) noted: “[a]lthough further evaluation is necessary, the potential of low-dose CT for use in the pediatric population in particular, as well as for screening in patients at high risk for developing lung cancer, is apparent.”

With accumulation of evidence on LDCT screening from studies in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the USPSTF updated their recommendation for lung cancer screening to a grade I (insufficient) recommendation and “found there was insufficient evidence to either recommend for or against routinely screening asymptomatic persons for lung cancer with either low-dose computed tomography (LDCT), chest x-ray (CXR), sputum cytology, or a combination of these tests (I statement)” (Humphrey et al., 2013). The USPSTF noted that “screening with LDCT, CXR, or sputum cytology can detect lung cancer at an earlier stage than lung cancer would be detected in an unscreened population; however, the USPSTF found poor evidence that any screening strategy for lung cancer decreases mortality” (USPSTF, 2004). As with many technologies, the initial studies on lung cancer screening with LDCT were observational case-control and cohort studies to generate hypotheses, show feasibility, and to identify the appropriate screening population.

In 2011, the results of the NCI-sponsored National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) were published. The NLST showed that people aged 55 to 74 years with a history of heavy smoking are 20 percent less likely to die from lung cancer if they are screened with low dose helical CT than with standard screening chest x-rays. Previous studies had shown that screening with standard chest x-rays does not reduce the mortality rate from lung cancer. The NLST identified risks as well as benefits. For example, people screened with low dose helical CT had a higher overall rate of false-positive results (that is, findings that appeared to be abnormal even though no cancer was present), leading to a higher rate of invasive procedures (such as bronchoscopy or biopsy), and serious complications from such invasive procedures, than those screened with standard x-rays. (NIH/NCI at http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/Detection/CT)

In 2014, Moyer and colleagues, on behalf of the USPSTF, released updated screening for lung cancer recommendations: “The USPSTF recommends annual screening for lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography in adults aged 55 to 80 years who have a 30 pack-year smoking history and currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years. Screening should be discontinued once a person has not smoked for 15 years or develops a health problem that substantially limits life expectancy or the ability or willingness to have curative lung surgery. (B recommendation)” (Moyer for the USPSTF, 2014).

III. History of Medicare Coverage

Pursuant to §1861(ddd) of the Social Security Act, the Secretary may add coverage of "additional preventive services" if certain statutory requirements are met. Our regulations provide:

§410.64 Additional preventive services

(a) Medicare Part B pays for additional preventive services not described in paragraph (1) or (3) of the definition of “preventive services” under §410.2, that identify medical conditions or risk factors for individuals if the Secretary determines through the national coverage determination process (as defined in section 1869(f)(1)(B) of the Act) that these services are all of the following:

(1) Reasonable and necessary for the prevention or early detection of illness or disability.

(2) Recommended with a grade of A or B by the United States Preventive Services Task Force.

(3) Appropriate for individuals entitled to benefits under part A or enrolled under Part B.

(b) In making determinations under paragraph (a) of this section regarding the coverage of a new preventive service, the Secretary may conduct an assessment of the relation between predicted outcomes and the expenditures for such services and may take into account the results of such an assessment in making such national coverage determinations.

Screening for lung cancer with LDCT is not currently covered under the Medicare program.

A. Current Request

CMS received two formal requests for a national coverage determination (NCD) for lung cancer screening with LDCT, one from Peter B. Bach (Director, Center for Health Policy and Outcomes, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center), and another from Ms. Laurie Fenton Ambrose (President & CEO, Lung Cancer Alliance). The formal request letters can be viewed via the tracking sheet for this NCA on the CMS website at http://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-tracking-sheet.aspx?NCAId=274.

B. Benefit Category

In order to be covered by Medicare, an item or service must fall within one or more benefit categories contained within Part A or Part B and must not be otherwise excluded from coverage. Since January 1, 2009, CMS is authorized to cover "additional preventive services" if certain statutory requirements are met as provided under §1861(ddd) of the Social Security Act.

IV. Timeline of Recent Activities

| Date |

Action |

| February 10, 2014 |

CMS initiates this national coverage analysis. A 30-day public comment period begins. |

March 12, 2014 |

The 30-day public comment period closed. |

April 30, 2014 |

CMS convened a meeting of the Medicare Evidence Development & Coverage Advisory Committee concerning the use of LDCT screening for lung cancer. |

November 10, 2014 |

CMS posted a proposed decision memorandum for screening for lung cancer with LDCT. A 30-day public comment period on the proposed decision begins. |

V. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Status

Currently, CT imaging systems and post-processing software go through the 510(k) process at the FDA to obtain clearance for commercial distribution. To obtain 510(k) clearance, the sponsor must demonstrate that the device is substantially equivalent to legally marketed predicate devices marketed in interstate commerce prior to May 28, 1976, the enactment date of the Medical Device Amendments, or to devices that have been reclassified in accordance with the provisions of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) that do not require approval of a premarket approval application (PMA).

CT devices were on the market prior to the passage of the Medical Device Amendments. They were originally indicated for general cross sectional imaging of the body. This includes the lungs and other specific organs. Subsequent modifications based on either additional built in processing or on post processing have expanded the breadth of CT images and with that their use.

Counseling services are not generally under the purview of the FDA.

VI. General Methodological Principles

When making national coverage determinations concerning additional preventive services, CMS applies the statutory criteria in § 1861(ddd) of the Social Security Act and evaluates relevant clinical evidence to determine whether or not the service is reasonable and necessary for the prevention or early detection of illness or disability, is recommended with a grade of A or B by the USPSTF, and is appropriate for individuals entitled to benefits under Part A or enrolled under Part B of the Medicare program.

CMS uses the initial public comments to inform its proposed decision. CMS responds in detail to the public comments on a proposed decision when issuing the final decision memorandum. Public comments sometimes cite published clinical evidence and give CMS useful information. Public comments that give information on unpublished evidence such as the results of individual practitioners or patients are less rigorous and therefore less useful for making a coverage determination. Public comments that contain personal health information will not be made available to the public.

VII. Evidence

A. Introduction

While a detailed discussion of screening is beyond the scope of this discussion, the basic parameters were established many years ago and are still well accepted to date. In 1968, Wilson and Jungner reported criteria to consider for screening:

Health outcomes, benefits, and risks are important considerations. As Cochrane and Holland (1971) further noted, evidence on health outcomes, i.e., "evidence that screening can alter the natural history of disease in a significant proportion of those screened," is important in the consideration of screening tests since individuals are asymptomatic and "the practitioner initiates screening procedures."

The evaluation of screening tests has been largely standardized in the medical and scientific communities, and the "value of a screening test may be assessed according to the following criteria:

- “Simplicity. In many screening programmes more than one test is used to detect one disease, and in a multiphasic programme the individual will be subjected to a number of tests within a short space of time. It is therefore essential that the tests used should be easy to administer and should be capable of use by para-medical and other personnel.

- Acceptability. As screening is in most instances voluntary and a high rate of co-operation is necessary in an efficient screening programme, it is important that tests should be acceptable to the subjects.

- Accuracy. The test should give a true measurement of the attribute under investigation.

- Cost. The expense of screening should be considered in relation to the benefits resulting from the early detection of disease, i.e., the severity of the disease, the advantages of treatment at an early stage and the probability of cure.

- Precision (sometimes called repeatability). The test should give consistent results in repeated trials.

- Sensitivity. This may be defined as the ability of the test to give a positive finding when the individual screened has the disease or abnormality under investigation.

- Specificity. This may be defined as the ability of the test to give a negative finding when the individual screened does not have the disease or abnormality under investigation”.

(Cochrane A and Holland W. Validation of screening procedures. British Medical Bulletin 1971;27(1):3-8. PMID: 5100948).

B. United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)

The USPSTF recommendation for lung cancer screening with LDCT (December 2013) states:

- The USPSTF recommends annual screening for lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography in adults ages 55 to 80 years who have a 30 pack-year smoking history and currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years. Screening should be discontinued once a person has not smoked for 15 years or develops a health problem that substantially limits life expectancy or the ability or willingness to have curative lung surgery. Grade: B recommendation.

The USPSTF assigns one of five letter grades to each of its recommendations (A, B, C, D, I). In July of 2012, the grade definitions were updated to reflect the change in definition of and suggestions for practice for the grade C recommendation.

The following tables from the USPSTF website provide the current grade definitions and descriptions of levels of certainty.

(http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/grades.htm)

Grade Definitions After July 2012

| Grade |

Definition |

Suggestions for Practice |

| A |

The USPSTF recommends the service. There is high certainty that the net benefit is substantial. |

Offer or provide this service. |

| B |

The USPSTF recommends the service. There is high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial. |

Offer or provide this service. |

| C |

The USPSTF recommends selectively offering or providing this service to individual patients based on professional judgment and patient preferences. There is at least moderate certainty that the net benefit is small. |

Offer or provide this service for selected patients depending on individual circumstances. |

| D |

The USPSTF recommends against the service. There is moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits. |

Discourage the use of this service. |

| I Statement |

The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of the service. Evidence is lacking, of poor quality, or conflicting, and the balance of benefits and harms cannot be determined. |

Read the clinical considerations section of USPSTF Recommendation Statement. If the service is offered, patients should understand the uncertainty about the balance of benefits and harms. |

| Level of Certainty |

Description |

|---|

| High |

The available evidence usually includes consistent results from well-designed, well-conducted studies in representative primary care populations. These studies assess the effects of the preventive service on health outcomes. This conclusion is therefore unlikely to be strongly affected by the results of future studies. |

| Moderate |

The available evidence is sufficient to determine the effects of the preventive service on health outcomes, but confidence in the estimate is constrained by such factors as:

The number, size, or quality of individual studies.

Inconsistency of findings across individual studies.

Limited generalizability of findings to routine primary care practice.

Lack of coherence in the chain of evidence.

As more information becomes available, the magnitude or direction of the observed effect could change, and this change may be large enough to alter the conclusion. |

Low |

The available evidence is insufficient to assess effects on health outcomes. Evidence is insufficient because of:

The limited number or size of studies.

Important flaws in study design or methods.

Inconsistency of findings across individual studies.

Gaps in the chain of evidence.

Findings not generalizable to routine primary care practice.

Lack of information on important health outcomes.

More information may allow estimation of effects on health outcomes. |

* The USPSTF defines certainty as "likelihood that the USPSTF assessment of the net benefit of a preventive service is correct." The net benefit is defined as benefit minus harm of the preventive service as implemented in a general, primary care population. The USPSTF assigns a certainty level based on the nature of the overall evidence available to assess the net benefit of a preventive service.

C. Literature Search

CMS searched PubMed from May 2004 to August 2014. General keywords included screening low dose CT and lung cancer. Publications that presented original data on screening were considered. Abstracts, animal studies and non-English language publications were excluded.

D. Discussion of Evidence

Question 1: Is the evidence sufficient to determine that screening for lung cancer with low dose computed tomography is recommended with a grade of A or B by the United States Preventive Services Task Force?

Question 2: Is the evidence sufficient to determine that screening for lung cancer with low dose computed tomography is reasonable and necessary for the prevention or early detection of illness or disability?

Question 3: Is the evidence sufficient to determine that screening for lung cancer with low dose computed tomography is appropriate for Medicare beneficiaries?

1. External technology assessments

Bach PB, Mirkin JN, Oliver TK, Azzoli CG, Berry DA, Brawley OW, Byers T, Colditz GA, Gould MK, Jett JR, Sabichi AL, Smith-Bindman R, Wood DE, Qaseem A, Detterbeck FC. Benefits and harms of CT screening for lung cancer: a systematic review. JAMA. 2012 Jun 13;307(22):2418-29. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5521. PMID: 22610500

Bach and colleagues reported the results of a systematic review of the evidence regarding the benefits and harms of lung cancer screening using LDCT. Studies were eligible “if they involved either an RCT using LDCT screening for lung cancer in one intervention group or a noncomparative cohort study of LDCT screening, provided they reported at least 1 of the following outcomes: lung cancer−specific or all-cause mortality, nodule detection rate, frequency of additional imaging, frequency of invasive diagnostic procedures (e.g., needle or bronchoscopic biopsy, surgical biopsy, surgical resection), complications from the evaluation of suspected lung cancer, or the rate of smoking cessation or reinitiation.” Searching from 1996 to April 2012, eight randomized trials and 13 cohort studies met criteria. Three trials provided evidence on mortality. The NLST (NLST team, 2012; n = 53,454) was a randomized trial that compared LDCT to chest radiography.

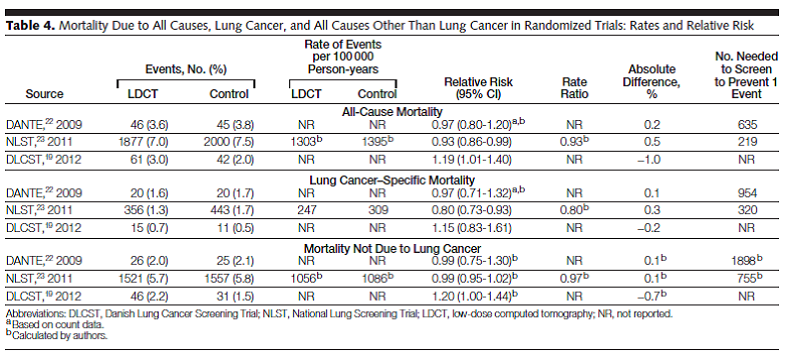

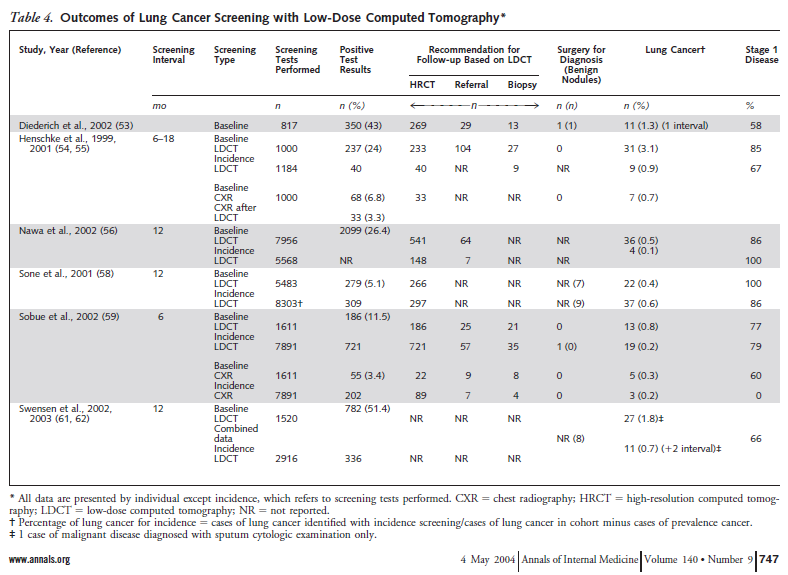

Table 4. Page 2422. JAMA. 2012 Jun 13;307(22):2418-29.

The authors concluded: “Screening a population of individuals at a substantially elevated risk of lung cancer most likely could be performed in a manner such that the benefits that accrue to a few individuals outweigh the harms that many will experience. However, there are substantial uncertainties regarding how to translate that conclusion into clinical practice.”

Humphrey LL, Teutsch S, Johnson M; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Lung cancer screening with sputum cytologic examination, chest radiography, and computed tomography: an update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2004 May 4;140(9):740-53. PMID: 15126259

Humphrey and colleagues reported the results of a systematic evidence review on lung cancer screening that provided the evidence base for the 2004 USPSTF recommendation. Studies on lung cancer screening using sputum cytology, chest radiology and computed tomography were reviewed. For LD CT, several observational studies were reviewed (presented in Table 4). There were no randomized controlled trials.

Table 4. Humphrey et al. Ann Intern Med. 2004 May 4;140(9):747. www.annals.org

Humphrey and colleagues concluded: “Current data do not support screening for lung cancer with any method. These data, however, are also insufficient to conclude that screening does not work, particularly in women. Two randomized trials of screening with chest radiography or low-dose CT are currently under way and will better inform lung cancer screening decisions.”

Humphrey LL, Deffebach M, Pappas M, Baumann C, Artis K, Mitchell JP, Zakher B, Fu R, Slatore CG. Screening for lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography: a systematic review to update the US Preventive services task force recommendation. Ann Intern Med. 2013 Sep 17;159(6):411-20. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-6-201309170-00690. PMID: 23897166

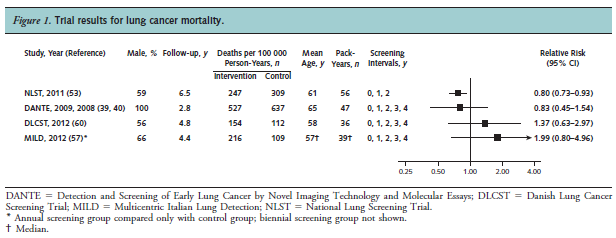

Humphrey and colleagues reported the results of a systematic review to re-evaluate the effectiveness of LDCT screening for lung cancer for the USPSTF. Trials and cohort studies that evaluated screening or treatment interventions for lung cancer that reported health outcomes were eligible. Searching from 2000 to May 2013, seven trials met criteria, with four trials that were included in the review because they reported results for both intervention and control groups. The NLST (NLST team, 2012; n = 53,454) compared LDCT to chest radiography. The authors stated: “One large good-quality trial reported that screening was associated with significant reductions in lung cancer (20 %) and all-cause (6.7 %) mortality. Three small European trials showed no benefit of screening. Harms included radiation exposure, overdiagnosis, and a high rate of false positive findings that typically were resolved with further imaging. Smoking cessation was not affected. Incidental findings were common.”

Figure 1. Page 414. Ann Intern Med. 2013 Sep 17;159(6):411-20.

The authors concluded: “Strong evidence shows that LDCT screening can reduce lung cancer and all-cause mortality. The harms associated with screening must be balanced with the benefits.”

Manser R, Lethaby A, Irving LB, Stone C, Byrnes G, Abramson MJ, Campbell D. Screening for lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Jun 21;6:CD001991. doi: 10.1002/14651858. CD001991.pub3. PMID: 23794187

Manser and colleagues reported the results of a Cochrane systematic review “to determine whether screening for lung cancer, using regular sputum examinations, chest radiography or CT scanning of the chest, reduces lung cancer mortality.” Controlled trials were included. This report updated the original review performed in 1999.

The authors reported: “We included nine trials in the review (eight randomised controlled studies and one controlled trial) with a total of 453,965 subjects. In one large study that included both smokers and non-smokers comparing annual chest x-ray screening with usual care there was no reduction in lung cancer mortality (RR 0.99, 95 % CI 0.91 to 1.07). In a meta-analysis of studies comparing different frequencies of chest x-ray screening, frequent screening with chest x-rays was associated with an 11 % relative increase in mortality from lung cancer compared with less frequent screening (RR 1.11, 95 % CI 1.00 to 1.23); however several of the trials included in this meta-analysis had potential methodological weaknesses. We observed a non-statistically significant trend to reduced mortality from lung cancer when screening with chest x-ray and sputum cytology was compared with chest x-ray alone (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.03). There was one large methodologically rigorous trial in high-risk smokers and ex-smokers (those aged 55 to 74 years with ≥ 30 pack-years of smoking and who quit ≤ 15 years prior to entry if ex-smokers) comparing annual low-dose CT screening with annual chest x-ray screening; in this study the relative risk of death from lung cancer was significantly reduced in the low-dose CT group (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.70 to 0.92).”

Page 19. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Jun 21;6:CD001991.

The authors concluded: “The current evidence does not support screening for lung cancer with chest radiography or sputum cytology. Annual low-dose CT screening is associated with a reduction in lung cancer mortality in high-risk smokers but further data are required on the cost effectiveness of screening and the relative harms and benefits of screening across a range of different risk groups and settings.”

Prosch H, Schaefer-Prokop C. Screening for lung cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2014 Mar;26(2):131-7. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000055. PMID: 24441507

Prosch and Schaefer-Prokop performed a systematic review of recent randomized controlled trials of lung cancer screening using LDCT. Included trials were the NLST, the Detection And screening of early lung cancer by Novel imaging TEchnology and molecular assays (DANTE) trial, the Multicentric Italian Lung Detection (MILD) trial, and the Danish Lung Cancer Screening Trial (DLCST). They reported: “The National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) was the first study that provided statistical evidence that LD-CT screening for lung cancer significantly reduces lung cancer mortality by 20 %. Three statistically underpowered European trials could not confirm the positive effect of LD-CT screening on lung cancer mortality. Major obstacles in lung cancer screening are overdiagnosis and the large number of false positive results. In the NLST, more than 24 % of the screens were positive, most of which (96.4 %) proved to be benign in nature. Optimized protocols for the workup of detected nodules may help to reduce the number of false-positive screens.” They further noted: “Long-term follow-up data are still anticipated on the European screening trials. Furthermore, data on the extent of the potential dangers of LD-CT screening, such as overdiagnosis, false-positive results, and the effect of cumulative radiation dose, have yet to be investigated thoroughly.”

Table 1. Page 133. Curr Opin Oncol. 2014 Mar;26(2):131-7.

2. Internal technology assessment

Infante M, Cavuto S, Lutman FR, Brambilla G, Chiesa G, Ceresoli G, Passera E, Angeli E, Chiarenza M, Aranzulla G, Cariboni U, Errico V, Inzirillo F, Bottoni E, Voulaz E, Alloisio M, Destro A, Roncalli M, Santoro A, Ravasi G; DANTE Study Group. A randomized study of lung cancer screening with spiral computed tomography: three-year results from the DANTE trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009 Sep 1;180(5):445-53. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200901-0076OC. Epub 2009 Jun 11. PMID: 19520905

Infante and colleagues reported results of the DANTE randomized trial designed “to explore the effect of screening with low-dose spiral computed tomography (LDCT) on lung cancer mortality.” Men aged 60 to 74 years with ≥ 20 pack-years smoking history were eligible. Patients with comorbidities that limited life expectancy to < 5 years, had a previous history of malignancy, or who were unable to comply with study protocols were excluded. Primary outcome was lung cancer mortality. Secondary outcomes included all-cause mortality, lung cancer incidence, stage and resectability. Between March 2001 and February 2006, 2811 participants were randomly assigned and 2472 were enrolled to yearly LDCT screening for 4 years (n = 1276) or yearly medical care control (n = 1196) at three sites in Italy. Mean age was 64 years. About 56 % were active smokers at baseline. Median follow-up was 33.7 months. Mean pack-years smoking was 47.

The authors reported 20 (1.6 %) lung cancer deaths in the LDCT group and 20 (1.7 %) in the control group (p = 0.84) and 46 (3.6 %) total deaths in the LDCT group and 45 (3.8 %) in the control group (p = 0.83). They concluded: “possible overdiagnosis, false positives, hazards of downstream investigation procedures, and cost issues make the results of randomized studies critically important in establishing a proper public health policy, and the final results from all ongoing randomized trials are awaited. In the meantime, continued application of current policies is supported by our data, and screening for LC with LDCT should not be advertised or proposed to high-risk subjects outside research programs.”

National Lung Screening Trial Research Team, Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, Black WC, Clapp JD, Fagerstrom RM, Gareen IF, Gatsonis C, Marcus PM, Sicks JD. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011 Aug 4;365(5):395-409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. Epub 2011 Jun 29. PMID: 21714641

The NCI-sponsored NLST was a randomized trial “to determine whether screening with low-dose CT, as compared with chest radiography, would reduce mortality from lung cancer among high-risk persons.” From August 2002 to April 2004, 53,454 individuals who were “between 55 and 74 years of age at the time of randomization, had a history of cigarette smoking of at least 30 pack-years, and, if former smokers, had quit within the previous 15 years” were enrolled at 33 U.S. centers and randomized to screening with 3 annual LDCT (n = 26,722) or three annual chest radiography (n = 26,732). Individuals who “had previously received a diagnosis of lung cancer, had undergone chest CT within 18 months before enrollment, had hemoptysis, or had an unexplained weight loss of more than 6.8 kg (15 lb) in the preceding year were excluded.” All screening tests were performed and interpreted according to protocol (NLST study design, 2011). It was “estimated that each NLST low-dose CT resulted in an average effective dose of 1.5 mSv, whereas the effective dose from conventional chest CT varies considerably in clinical practice but is on the order of 8 mSv” (NLST study design, 2011). The primary outcome was lung cancer mortality. Secondary outcomes included all-cause mortality and lung cancer incidence. Median age was approximately 61 years with 26.6 % of participants being 65 years and older. Men comprised 59 % of the study. Ninety one percent were white. Forty eight percent were current smokers. Median follow-up was 6.5 years. Adherence to all three screenings was 95 % in the LDCT group and 93 % in the radiography group.

The authors reported “[t]here were 247 deaths from lung cancer per 100,000 person-years in the low-dose CT group and 309 deaths per 100,000 person-years in the radiography group, representing a relative reduction in mortality from lung cancer with low-dose CT screening of 20.0 % (95 % CI, 6.8 to 26.7; P = 0.004). The rate of death from any cause was reduced in the low-dose CT group, as compared with the radiography group, by 6.7 % (95 % CI, 1.2 to 13.6; P = 0.02).”

Table 7. page 407. N Engl J Med. 2011 Aug 4;365(5):395-409.

The authors concluded “[s]creening with the use of low-dose CT reduces mortality from lung cancer.”

Pastorino U, Rossi M, Rosato V, Marchianò A, Sverzellati N, Morosi C, Fabbri A, Galeone C, Negri E, Sozzi G, Pelosi G, La Vecchia C. Annual or biennial CT screening versus observation in heavy smokers: 5-year results of the MILD trial. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2012 May;21(3):308-15. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e328351e1b6. PMID: 22465911

Pastorino and colleagues reported the results of the MILD randomized trial “to evaluate the impact on mortality of early lung cancer detection through LDCT at annual or biennial intervals versus no screening.” Individuals who were ≥ 49 years of age with ≥ 20 pack-year smoking history and no history of cancer within past 5 years were included. No other exclusion criteria were reported. From September 2005 to January 2011, 4099 participants were enrolled and randomly assigned to annual LDCT screening (n=1190), biennial LDCT screening (n=1186) and no screening control group with smoking cessation interventions and pulmonary function tests (n=1723) at 1 site in Italy (trial was initially designed to be conducted at multiple centers but limited to one site due to funding). Primary outcome was lung cancer mortality. Secondary outcomes included all-cause mortality and lung cancer incidence. Median age was 57 years. Men comprised 67 % of the study population. At baseline, there were more current smokers in the control group (89.7 %) compared to the LDCT screening groups (68.3 % annual and 68.9 % biennial). Median pack-years smoking was 39.

The authors reported: “The cumulative 5-year lung cancer incidence rate was 311/100 000 in the control group, 457 in the biennial, and 620 in the annual LDCT group (P = 0.036); lung cancer mortality rates were 109, 109, and 216/100 000 (P = 0.21), and total mortality rates were 310, 363, and 558/100 000, respectively (P = 0.13).” They concluded: “There was no evidence of a protective effect of annual or biennial LDCT screening. Furthermore, a meta-analysis of the four published randomized trials [DANTE (Infante), DLCST (Saghir), MILD, NLST] showed similar overall mortality in the LDCT arms compared with the control arm.” “The effect on lung cancer mortality remains significant (relative risk 0.82, 95 % CI 0.73–0.93) but the value of disease-specific mortality as the only endpoint appears questionable for two reasons: the assessment of the real cause of death can be very difficult in heavy smokers because of complex comorbidity; a shift in the cause of death from one disease to another is frequent in screened populations and hence potentially misleading.”

Saghir Z1, Dirksen A, Ashraf H, Bach KS, Brodersen J, Clementsen PF, Døssing M, Hansen H, Kofoed KF, Larsen KR, Mortensen J, Rasmussen JF, Seersholm N, Skov BG, Thorsen H, Tønnesen P, Pedersen JH. CT screening for lung cancer brings forward early disease. The randomised Danish Lung Cancer Screening Trial: status after five annual screening rounds with low-dose CT. Thorax. 2012 Apr;67(4):296-301. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200736. Epub 2012 Jan 27. PMID: 22286927.

Saghir and colleagues reported the results of a randomized controlled trial “to evaluate if annual low dose CT screening [for 5 annual screenings] can reduce lung cancer mortality by more than 25 %” (Pederson, 2009). Inclusion criteria were age 50-70 years, current or former smokers with at least 20 pack-years of smoking history, ability to climb two flights of stairs (36 steps) without pausing. Exclusion criteria were “weight over 130 kg, history of cancer diagnosis and treatment, lung tuberculosis, illness that would shorten life expectancy to < 10 years and chest CT received during the last year for any reason.” Primary outcome was lung cancer mortality. Secondary outcomes included overall mortality, number of lung cancer, stage and health economic evaluations. From October 2004 to March 2006, 4104 participants were enrolled and randomly assigned to CT screening group (five annual LDCT; n = 2052) or control group (no screening) (n = 2052) at one site in Denmark. “All participants had an annual visit at the screening clinic, where lung function tests were performed, and questionnaires concerning health, lifestyle, smoking habits and psychosocial consequences of screening were completed.” Median age was not reported (peak number of patients were between 55-59 years). Men comprised 55 % of the study population. Median follow-up was 4.81 years.

The authors reported: “At the end of screening, 61 patients died in the screening group and 42 in the control group (p = 0.059). 15 and 11 died of lung cancer, respectively (p = 0.428).” They concluded: “CT screening for lung cancer brings forward early disease, and at this point no stage shift or reduction in mortality was observed. More lung cancers were diagnosed in the screening group, indicating some degree of overdiagnosis and need for longer follow-up.”

3. Medicare Evidence Development & Coverage Advisory Committee (MEDCAC)

On April 30, 2014, a Medicare Evidence Development & Coverage Advisory Committee (MEDCAC) meeting was convened to discuss the body of evidence, hear presentations, consider public comments, and make recommendations to CMS regarding the currently available evidence related to early detection (screening) of lung cancer with LDCT in asymptomatic adults with histories of significant smoking. A CMS representative presented a basic background of lung cancer screening; how Medicare's consideration of preventive services is statutorily different than CMS’ consideration of evaluation and management services; and read the voting and discussion questions that would be considered by the panel. The panel heard presentations from four invited guest speakers, 16 scheduled speakers, and four members of the public.

The eight voting members on the panel voted on three questions (listed below) using a scale of one to five, with one representing a low confidence vote and one representing a high confidence vote. An average voting score of 2.5 represented intermediate confidence. The scores of the voting panel members were recorded and the average was calculated.

- How confident are you that there is adequate evidence to determine if the benefits outweigh the harms of lung cancer screening with LDCT [CT acquisition variables set to reduce exposure to an average effective dose of 1.5 mSv…] in the Medicare population?

- How confident are you that the harms of lung cancer screening with LDCT (average effective dose of 1.5 mSv) if implemented in the Medicare population will be minimized?

- How confident are you that clinically significant evidence gaps remain regarding the use of LDCT (average effective dose of 1.5 mSv) for lung cancer screening in the Medicare population outside a clinical trial?

- Average score: 4.67. Since the resulting average voting score on this question showed at least intermediate confidence (score ≥ 2.5 above), the panel was asked to discuss any significant gaps identified and how CMS might support their closure.

Information about the meeting, including the agenda, presentations from speakers, transcripts, and results of the voting questions are available on the CMS Website at: http://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/medcac-meeting-details.aspx?MEDCACId=68.

4. Evidence-based guidelines

Detterbeck FC, Mazzone PJ, Naidich DP, Bach PB. Screening for lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013 May;143(5 Suppl):e78S-92S. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2350. PMID: 23649455

Detterbeck and colleagues reported the American College of Chest Physicians guidelines based in part on the systematic review by Bach (2012). Specifically for lung cancer screening with LDCT:

“3.4.1. For smokers and former smokers who are age 55 to 74 and who have smoked for 30 pack-years or more and either continue to smoke or have quit within the past 15 years, we suggest that annual screening with LDCT should be offered over both annual screening with CXR or no screening, but only in settings that can deliver the comprehensive care provided to NLST participants (Grade 2B).” The guidelines also included the following remarks.

- “Counseling should include a complete description of potential benefits and harms, so the individual can decide whether to undergo LDCT screening.”

- “Screening should be conducted in a center similar to those where the NLST was conducted, with multidisciplinary coordinated care and a comprehensive process for screening, image interpretation, management of findings, and evaluation and treatment of potential cancers.”

- “A number of important questions about screening could be addressed if individuals who are screened for lung cancer are entered into a registry that captures data on follow-up testing, radiation exposure, patient experience, and smoking behavior.”

- “Quality metrics should be developed such as those in use for mammography screening, which could help enhance the benefits and minimize the harm for individuals who undergo screening.”

- “Screening for lung cancer is not a substitute for stopping smoking. The most important thing patients can do to prevent lung cancer is not smoke.”

- “The most effective duration or frequency of screening is not known.”

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Lung cancer screening: recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2004 May 4;140(9):738-9. PMID: 15126258

In 2004, the USPSTF concluded that “the evidence is sufficient to recommend for or against screening asymptomatic persons for lung cancer with either low-dose computerized tomography (LDCT), chest x-ray (CXR), sputum cytology, or a combination of these tests. This is a grade I recommendation.” As reported in the analysis, “The USPSTF found fair evidence that screening with LDCT, CXR or sputum cytology can detect lung cancer at an earlier stage than lung cancer would be detected in an unscreened population; however, the USPSTF found poor evidence that any screening strategy for lung cancer decreases mortality. Because of the invasive nature of diagnostic testing and the possibility of a high number of false-positive tests in certain populations, there is potential for significant harms from screening. Therefore, the USPSTF could not determine the balance between the benefits and harms of screening for lung cancer.”

Moyer VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for lung cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014 Mar 4;160(5):330-8. doi: 10.7326/M13-2771. PMID: 24378917

Moyer, on behalf of the USPSTF, reported a revised recommendation on lung cancer screening based on the review by Humphrey, et al. (2013) (see external technology assessments section above), concluding that “[t]he USPSTF recommends annual screening for lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) in adults aged 55 to 80 years who have a 30 pack-year smoking history and currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years. Screening should be discontinued once a person has not smoked for 15 years or develops a health problem that substantially limits life expectancy or the ability or willingness to have curative lung surgery. (B recommendation)”

Wood DE, Eapen GA, Ettinger DS, Hou L, Jackman D, Kazerooni E, Klippenstein D, Lackner RP, Leard L, Leung AN, Massion PP, Meyers BF, Munden RF, Otterson GA, Peairs K, Pipavath S, Pratt-Pozo C, Reddy C, Reid ME, Rotter AJ, Schabath MB, Sequist LV, Tong BC, Travis WD, Unger M, Yang SC. Lung cancer screening. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012 Feb;10(2):240-65. PMID: 22308518

Wood and colleagues reported the National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®) guideline and consensus statement. The lung cancer panel recommended “helical LDCT screening for select patients at high risk for lung cancer based on the NLST results, nonrandomized studies, and observational data.” (2012)

Page 242. © JNCCN–Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network | Volume 10 Number 2 | February 2012.

5. Professional Society Recommendations

American Academy of Family Physicians. Lung cancer clinical recommendations. Accessed May 12, 2014. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/lung-cancer.html.

The AAFP concluded that “the evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against screening for lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) in persons at high risk for lung cancer based on age and smoking history. (2013) (Grade: I recommendation)”

Wender R, Fontham ET, Barrera E Jr, Colditz GA, Church TR, Ettinger DS, Etzioni R, Flowers CR, Gazelle GS, Kelsey DK, LaMonte SJ, Michaelson JS, Oeffinger KC, Shih YC, Sullivan DC, Travis W, Walter L, Wolf AM, Brawley OW, Smith RA. American Cancer Society lung cancer screening guidelines. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013 Mar-Apr;63(2):107-17. doi: 10.3322/caac.21172. Epub 2013 Jan 11. PMID: 23315954

In 2013, Wender and colleagues, on behalf of the American Cancer Society, released lung cancer screening guidelines: “Findings from the National Cancer Institute’s National Lung Screening Trial established that lung cancer mortality in specific high-risk groups can be reduced by annual screening with low-dose computed tomography. These findings indicate that the adoption of lung cancer screening could save many lives. Based on the results of the National Lung Screening Trial, the American Cancer Society is issuing an initial guideline for lung cancer screening. This guideline recommends that clinicians with access to high-volume, high-quality lung cancer screening and treatment centers should initiate a discussion about screening with apparently healthy patients aged 55 years to 74 years who have at least a 30-pack-year smoking history and who currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years. A process of informed and shared decision making with a clinician related to the potential benefits, limitations, and harms associated with screening for lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography should occur before any decision is made to initiate lung cancer screening. Smoking cessation counseling remains a high priority for clinical attention in discussions with current smokers, who should be informed of their continuing risk of lung cancer. Screening should not be viewed as an alternative to smoking cessation.”

(American Cancer Society:http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/webcontent/acspc-039558-pdf.pdf))

“The American Cancer Society has thoroughly reviewed the subject of lung cancer screening and issued guidelines that are aimed at doctors and other health care providers:

Patients should be asked about their smoking history. Patients who meet ALL of the following criteria may be candidates for lung cancer screening:

- 55 to 74 years old

- In fairly good health (discussed further down)

- Have at least a 30 pack-year smoking history (Someone who smoked a pack of cigarettes per day for 30 years has a 30 pack-year smoking history, as does someone who smoked 2 packs a day for 10 years and then a pack a day for another 10 years.)

- Are either still smoking or have quit smoking within the last 15 years.

These criteria were based on what was used in the NLST.

Doctors should talk to these patients about the benefits, limitations, and potential harms of lung cancer screening. Screening should only be done at facilities that have the right type of CT scan and that have a great deal of experience in LDCT scans for lung cancer screening. The facility should also have a team of specialists that can provide the appropriate care and follow-up of patients with abnormal results on the scans.

Screening is meant to find cancer in people who do not have symptoms of the disease. People who already have symptoms that might be caused by lung cancer may need tests such as CT scans to find the underlying cause, which in some cases may be cancer. Still, this kind of testing is for diagnosis and is not the same as screening. Some of the possible symptoms of lung cancer that kept people out of the NLST were coughing up blood and weight loss without trying. To get the most potential benefit from screening, patients need to be in good health. For example, they need to be able to have surgery and other treatments to try to cure lung cancer if it is found. Patients who require home oxygen therapy most likely could not withstand having part of a lung removed, and so are not candidates for screening. Patients with other serious medical problems that would shorten their lives or keep them from having surgery may also not be able to benefit enough from screening for it to be worth the risks, and so should also not be screened. Metal implants in the chest (like pacemakers) or back (like rods in the spine) can interfere with x-rays and lead to poor quality CT images of the lungs. People with these types of implants were also kept out of the NLST, and so should not be screened with CT scans for lung cancer according to the ACS guidelines. People who have been treated for lung cancer often have follow-up tests, including CT scans to see if the cancer has come back or spread. This is called surveillance and is not the same as screening. (People with a prior history of lung cancer were not eligible for the NLST.)”

We note that the American College of Radiology commented on the American Cancer Society screening guidelines (described earlier).

“The American College of Radiology (ACR) acknowledges the importance of the new American Cancer Society recommendations for lung cancer screening using computed tomography (CT) scans. The ACR stresses that guidelines and practice standards are needed, and must be appropriately implemented, to ensure that patients nationwide have access to uniform, quality care and can expect a similar life-saving benefit from these exams as demonstrated in clinical trials.

Such guidelines must take into consideration the potential for false positives, incidental findings and other consequences that might negatively impact patients. The ACR is working on a practice guideline as well as ACR Appropriateness Criteria® based on thorough vetting of the peer reviewed literature.”

‘We continue to push forward in our work on standards regarding how and when these screening exams are conducted to help make sure that those who should be screened can do so regardless of where they live, but these standards need adequate time to be finalized to support a robust screening program that will provide the life-saving results that everyone wants,’ said Paul Ellenbogen, MD, FACR, chair of the ACR Board of Chancellors.”

The ACR supports the use of techniques shown to significantly reduce the number of people who die each year from lung cancer. Recent evidence, particularly results of the National Lung Cancer Screening Trial (NLST), has shown that CT lung cancer screening is appropriate when performed in the context of careful patient selection and follow-up.

However, barriers to widespread access to CT lung cancer screening remain — including acceptance of the cost-effectiveness of such a national screening program by Medicare and private insurers and associated coverage of these exams. While some insurers cover these exams, many may be waiting for the cost-effectiveness data from the NLST to be published later this year.”

American Lung Association. Providing guidance on lung cancer screening to patients and physicians. April 23, 2012. Accessed May 12, 2014. Available at: http://www.lung.org/lung-disease/lung-cancer/lung-cancer-screening-guidelines/lung-cancer-screening.pdf

The American Lung Association “convened a Lung Cancer Screening Committee, chaired by Jonathan Samet, MD, MS, to review the current scientific evidence on cancer screening in order to assist the ALA in offering the best possible guidance to the public and those suffering from lung disease.” “The Committee acknowledges that cancer screening is associated with both benefits and risks and unfortunately, the NLST could not answer a number of questions on the advantages and safety of screening in the general population. In spite of this, the Committee provides the following interim recommendations:

- The best way to prevent lung cancer caused by tobacco use is to never start or quit smoking.

- Low-dose CT screening should be recommended for those people who meet NLST criteria:

- current or former smokers, aged 55 to 74 years

- a smoking history of at least 30 pack-years

- no history of lung cancer

- Individuals should not receive a chest X-ray for lung cancer screening

- the difference between a screening process and a diagnostic test

- the benefits, risks and costs (emotional, physical and economic)

- that not all lung cancers will be detected through use of low dose CT scanning

- Low-dose CT screening should NOT be recommended for everyone

- ALA should develop public health materials describing the lung cancer screening process in order to assist patients in talking with their doctors. This educational portfolio should include information that explains and clarifies for the public:

- A call to action should be issued to hospitals and screening centers to:

- establish ethical policies for advertising and promoting lung cancer CT screening services

- develop educational materials to assist patients in having careful and thoughtful discussions between patients and their physicians regarding lung cancer screening

- provide lung cancer screening services with access to multidisciplinary that can deliver the needed follow-up for evaluation of nodules.”

Jaklitsch MT, Jacobson FL, Austin JH, Field JK, Jett JR, Keshavjee S, MacMahon H, Mulshine JL, Munden RF, Salgia R, Strauss GM, Swanson SJ, Travis WD, Sugarbaker DJ. The American Association for Thoracic Surgery guidelines for lung cancer screening using low-dose computed tomography scans for lung cancer survivors and other high-risk groups. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012 Jul;144(1):33-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.05.060. PMID: 22710039

Jaklitsch and colleagues reported American Association for Thoracic Surgery guidelines for lung cancer screening using LDCT. “The American Association for Thoracic Surgery guidelines call for annual lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography screening for North Americans from age 55 to 79 years with a 30 pack-year history of smoking. Long-term lung cancer survivors should have annual low-dose computed tomography to detect second primary lung cancer until the age of 79 years. Annual low-dose computed tomography lung cancer screening should be offered starting at age 50 years with a 20 pack-year history if there is an additional cumulative risk of developing lung cancer of 5 % or greater over the following 5 years. Lung cancer screening requires participation by a subspecialty-qualified team. The American Association for Thoracic Surgery will continue engagement with other specialty societies to refine future screening guidelines.”

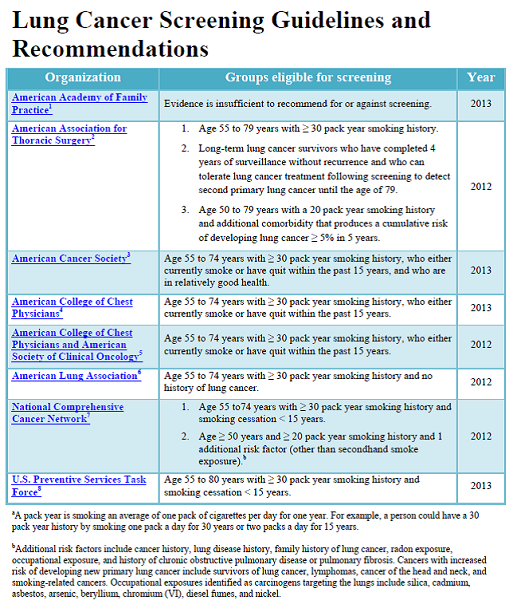

CDC Lung Cancer Screening Guidelines and Recommendations

(http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/lung/pdf/guidelines.pdf)

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention made available on their website a summary of existing guidelines and recommendations related to lung cancer screening (see image below).

Available at http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/lung/pdf/guidelines.pdf

6. Modeling

de Koning HJ, Meza R, Plevritis SK, ten Haaf K, Munshi VN, Jeon J, Erdogan SA, Kong CY, Han SS, van Rosmalen J, Choi SE, Pinsky PF, Berrington de Gonzalez A, Berg CD, Black WC, Tammemägi MC, Hazelton WD, Feuer EJ, McMahon PM. Benefits and harms of computed tomography lung cancer screening strategies: a comparative modeling study for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2014 Mar 4;160(5):311-20. doi: 10.7326/M13-2316. PMID: 24379002

de Koning and colleagues reported the results of simulation models of LDCT lung cancer screening scenarios “to estimate future harms and benefits of lung cancer screening and identify a set of possible efficient lung cancer screening policies by using 5 separately developed microsimulation models calibrated to the 2 largest randomized controlled trials on lung cancer screening.” Five simulation models [Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands (model E); Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington (model F); the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts (model M); Stanford University in Stanford, California (model S); and the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan (model U)] were calibrated according to the NLST and the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial (PLCO). In all models, 100 % adherence was assumed.

The investigators reported: “The most advantageous strategy was annual screening from ages 55 through 80 years for ever smokers with a smoking history of at least 30 pack-years and ex-smokers with less than 15 years since quitting. It would lead to 50 % (model ranges, 45 % to 54) of cases of cancer being detected at an early stage (stage I/II), 575 screenings examinations per lung cancer death averted, a 14 % (range, 8.2 % to 23.5 %) reduction in lung cancer mortality, 497 lung cancer deaths averted, and 5250 life-years gained per the 100 000-member cohort. Harms would include 67 550 false-positive test results, 910 biopsies or surgeries for benign lesions, and 190 overdiagnosed cases of cancer (3.7 % of all cases of lung cancer [model ranges, 1.4 % to 8.3 %]).”

It is unclear why and how the PLCO (Oken, 2011), which evaluated chest x-ray screening, was used in model calibration. The simulation of LDCT screening appears to be based entirely on the NLST results and parameters since no other trial on LDCT was included. Sensitivity analysis of harms was specifically reported. Specific harms of follow-up were not listed.

7. Public Comments

During the initial 30-day comment period (2/10/2014 – 3/12/2014), CMS received 330 comments from various entities including providers, advocacy organizations, academic institutions, trade associations, and the general public. Of the comments received, 278 commenters advocated for coverage of lung cancer screening with LDCT, 27 supported coverage with conditions, 2 opposed, and 23 did not express a position.

The comments received during the initial 30-day public comment period can be viewed in their entirety on the CMS Website at: http://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-view-public-comments.aspx?NCAId=274

VIII. Analysis

National coverage determinations (NCDs) are determinations by the Secretary with respect to whether or not a particular item or service is covered nationally under title XVIII of the Social Security Act (§ 1869(f)(1)(B)). In order to be covered by Medicare, an item or service must fall within one or more benefit categories contained within Part A or Part B, and must not be otherwise excluded from coverage. Since January 1, 2009, CMS is authorized to cover "additional preventive services" (see Section III above) if certain statutory requirements are met as provided under § 1861(ddd) of the Social Security Act. Regulations at 42 C.F.R. § 410.64 provide:

(a) Medicare Part B pays for additional preventive services not described in paragraph (1) or (3) of the definition of “preventive services” under §410.2, that identify medical conditions or risk factors for individuals if the Secretary determines through the national coverage determination process (as defined in section 1869(f)(1)(B) of the Act) that these services are all of the following:

(1) Reasonable and necessary for the prevention or early detection of illness or disability.

(2) Recommended with a grade of A or B by the United States Preventive Services Task Force.

(3) Appropriate for individuals entitled to benefits under part A or enrolled under Part B.

(b) In making determinations under paragraph (a) of this section regarding the coverage of a new preventive service, the Secretary may conduct an assessment of the relation between predicted outcomes and the expenditures for such services and may take into account the results of such an assessment in making such national coverage determinations.

Question 1: Is the evidence sufficient to determine that screening for lung cancer with low dose computed tomography is recommended with a grade of A or B by the United States Preventive Services Task Force?

In 2014, Moyer and colleagues, on behalf of the USPSTF, reported: “The USPSTF recommends annual screening for lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography in adults aged 55 to 80 years who have a 30 pack-year smoking history and currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years. Screening should be discontinued once a person has not smoked for 15 years or develops a health problem that substantially limits life expectancy or the ability or willingness to have curative lung surgery. (B recommendation)” (Moyer, 2014).

Prior to the current recommendation, the USPSTF evaluated lung cancer screening in 1996 (grade D) and in 2004 (grade I – consistent with current I statement) based upon 6 observational studies (Humphrey, 2004). The change in recommendation was based upon four trials (DANTE, DLSCT, MILD, NLST) (Humphrey, 2011). Net benefit of screening was supported primarily by NLST (for individuals aged 55 to 74 years who have ≥ 30 pack-year smoking histories and current smokers or have quit in the past 15 years). Extension of the upper age from 74 to 80 years was based upon modeling only, with no empirical data.

In the 2014 considerations, the USPSTF specifically noted recommendations for:

“Implementation of a Lung Cancer Screening Program

Screening Eligibility, Screening Intervals, and Starting and Stopping Ages

The NLST, the largest RCT to date with more than 50,000 patients, enrolled participants aged 55 to 74 years at the time of randomization who had a tobacco use history of at least 30 pack-years and were current smokers or had quit within the past 15 years (4). The USPSTF recommends extending the program used in the NLST through age 80 years. Screening should be discontinued once the person has not smoked for 15 years.

The NLST enrolled generally healthy persons, and the findings may not accurately reflect the balance of benefits and harms in those with comorbid conditions. The USPSTF recommends discontinuing screening if a person develops a health problem that substantially limits life expectancy or the ability or willingness to have curative lung surgery.

Clinicians will encounter patients who are interested in screening but do not meet the criteria of high risk for lung cancer as described previously. The balance of benefits and harms of screening may be unfavorable in these lower-risk patients. Current evidence is lacking on the net benefit of expanding LDCT screening to include lower-risk patients. It is important that persons who are at lower risk for lung cancer be aware of the potential harms of screening. Future improvements in risk assessment tools will help clinicians better individualize patients' risks (6).

Smoking Cessation Counseling

All persons enrolled in a screening program should receive smoking cessation interventions. To be consistent with the USPSTF recommendation on counseling and interventions to prevent tobacco use and tobacco-caused disease, persons who are referred to a lung cancer screening program through primary care should receive these interventions before referral. Because many persons may enter screening through pathways besides referral from primary care, the USPSTF encourages incorporating such interventions into the screening program.

Shared Decision Making

Shared decision making is important for persons within the population for whom screening is recommended. The benefit of screening varies with risk because persons who are at higher risk because of smoking history or other risk factors are more likely to benefit. Screening cannot prevent most lung cancer deaths, and smoking cessation remains essential. Lung cancer screening has substantial harms, most notably the risk for false-positive results and incidental findings that lead to a cascade of testing and treatment that may result in more harms, including the anxiety of living with a lesion that may be cancer. Overdiagnosis of lung cancer and the risks of radiation are real harms, although their magnitude is uncertain. The decision to begin screening should be the result of a thorough discussion of the possible benefits, limitations, and known and uncertain harms.

Standardization of LDCT Screening and Follow-Up of Abnormal Findings

The evidence for the effectiveness of screening for lung cancer with LDCT comes from RCTs done in large academic medical centers with expertise in using LDCT and diagnosing and managing abnormal lung lesions. Clinical settings that have high rates of diagnostic accuracy using LDCT, appropriate follow-up protocols for positive results, and clear criteria for doing invasive procedures are more likely to duplicate the results found in trials. The USPSTF supports adherence to quality standards for LDCT (8) and establishing protocols to follow up abnormal results, such as those proposed by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (7). A mechanism should be implemented to ensure adherence to these standards.

In the context of substantial uncertainty about how best to manage individual lesions, as well as the magnitude of some of the harms of screening, the USPSTF encourages the development of a registry to ensure that appropriate data are collected from screening programs to foster continuous improvement over time. The registry should also compile data on incidental findings and the testing and interventions that occur as a result of these findings.”

Question 2: Is the evidence sufficient to determine that screening for lung cancer with low dose computed tomography is reasonable and necessary for the prevention or early detection of illness or disability?

Since 2004, four trials (DANTE, DLSCT, MILD, NLST) evaluated lung cancer screening using LDCT. One large trial (NLST, 2011; n = 53,454) showed three annual LDCT screenings of individuals aged 55 to 74 years who have ≥ 30 pack-year smoking history and are current smokers or have quit in the past 15 years reduced lung cancer mortality. Two smaller trials (DANTE, 2009, n = 2472; DLSCT, 2012, n = 4104) did not find a significant difference in lung cancer mortality between LDCT screening compared to control (no screening). One trial compared annual to biennial screening and found no significant difference in lung cancer mortality (MILD, 2012, n = 4099).

The NLST is the only trial to demonstrate benefit of lung cancer screening with LDCT. It was a well conducted, large multicenter trial performed at 33 centers with trained and approved radiologists and follow-up evaluation at experienced centers. Investigators noted: “the NLST was conducted at a variety of medical institutions, many of which are recognized for their expertise in radiology and in the diagnosis and treatment of cancer. It is possible that community facilities will be less prepared to undertake screening programs and the medical care that must be associated with them.”